The following are quotes from our extensive collection of Arthur Griffith’s writings. One of the most prolific Irish journalists of his time and a founding father of the early Irish state, his writings are of great interest to those researching the early Sinn Féin movement. You can read his writings here.

Nationalism

We trust we have made ourselves perfectly plain. We have not endeavoured to do aught else. Lest there might be a doubt in any mind, we will say that we accept the Nationalism of ’98, ’48 and ’67 as the true Nationalism and Grattan’s cry, “Live Ireland—Perish the Empire!” as the watchword of patriotism.

—The United Irishman, March 4, 1899.

Let every Irishman form in his own mind an ideal Ireland; Irish in everything it says, Irish in every note it sings, Irish in its social life, Irish in everything it buys; and then, let him act up to his ideal as far as he possibly can. If he does this, the future of the country will be safe, be our period of suspense short or be it long.

—The United Irishman, June 24, 1899.

For years past the word Nationalist has been sadly abused, and the man who shouted for cheap land and the man who yelled for Home Rule told the simple people they were Nationalists and the people believed them. Let it be clearly understood that Home Ruler and Nationalist mean wholly opposite and irreconcilable things. The Home Ruler acknowledges the right of England to govern this country, while he demands facilities for dealing with purely local Irish matters in Ireland, and for that purpose seeks the erection of a legislative body in Dublin. In return for this concession, for so he terms it, he guarantees the loyalty and devotion of the Irish people to England, and their readiness to share in the turpitude of the British Empire. The Nationalist, on the other hand, totally rejects the claim of England or any other country to rule over or interfere with the destinies of Ireland.

—The United Irishman, August 4, 1900.

The lesson must be taught by a self-governing Ireland, gently if it may and harshly if it must, that the nation is not any man’s nor any generation’s to barter, that it is a trust from our ancestors which we must transmit to our posterity—that no man or body of men can claim to be above the nation, and that the nation is greater than all its units. Thus only we can perpetuate ourselves and live and die in honour.

—Sinn Féin, November 29, 1913.

As for ourselves, we have no grievance against the Almighty in making us Irish rather than English. We believe Ireland to be one of the finest countries in the world—we believe the Irish, who have survived 700 years of Atrocities that are not fiction and kept their ideals through it all, to be in essence one of the greatest people who have appeared on the earth. We believe such a people restored to political and national liberty must become torches and exemplars of humankind. We believe, in short, that Ireland will be again one of these days what it was in a former day—the Light of the World, and that the chief business of every Irishman is to hasten the Day.

—Nationality, June 19, 1915.

The right of an Irish Nationalist to hold and champion any view he pleases, extraneous to Irish Nationalism, is absolute. The right of the Irish to political independence never was, is not, and never can be dependent upon the admission of equal right in all other peoples. It is based on no theory of, and dependable in no wise for its existence or justification on the ‘Rights of Man,’ it is independent of theories of government and doctrines of philanthropy and Universalism. He who holds Ireland a nation and all means lawful to restore her the full and free exercise of national liberties thereby no more commits himself to the theory that black equals white, that kingship is immoral, or that society has a duty to reform its enemies than he commits himself to the belief that sunshine is extractable from cucumbers.

—Preface to Jail Journal by John Mitchel, 1913 edition.

We reject with contempt the idea that a prosperous Ireland would cease to be a national Ireland. We believe if Irish Nationalism be so poor a plant that it cannot thrive except on grievances it deserves to perish.

—Sinn Féin, October 10, 1908.

Nationalism is the prime political truth and even its old enemies are realising now that through it, evolution and progress must work. The State and the Nation are neither necessarily enemies nor necessarily friends. The State may oppress—the Nation always frees. Loyalty to the Nation may dictate rebellion against the State, and loyalty to the State may be treason to the Nation. But where State and Nation go hand in hand there is the surest guarantee for political progress. In Ireland the Nation and the State are hostile—therefore, there can be no peace in Ireland until the Nation dominates the State or the Nation be extinguished.

—Sinn Féin, November 18, 1911.

Imperialism

Ireland and the Empire are incompatible. One cannot be an African ‘civiliser’ and an Irish Nationalist; one cannot trample on the rights of other people and consistently demand his own.

—The United Irishman, March 4, 1899.

Imperialism as a general policy is merely an exchangeable term for the advance of civilisation. It is the embodiment of human progress carried out and polished by the attritions of nations. But if it is to succeed and develop humanely and efficaciously it must not trespass on the real, unquestionable domain of nationhood. No nation ought to be yoked to the car of Imperialism that does not share in the common benefit. And every nation has a right and duty to compete with its fellows, and to secure the fullest influence in bearing the banner of progress beyond the present limits that bar the advance of civilisation.

—The United Irishman, June 17, 1899.

There are two reasons why British Imperialism should lack proselytes. The first is an Irish reason—it is robbery plus murder. The second is an English one—it won’t pay. The experiment of trying to coin dividends out of Boer blood ruined it.

—The United Irishman, February 2, 1901.

Irishmen who accept the idea of Imperialism as true, and who preach it to their countrymen as if it were a new-found gospel, waste their energy so long as the Imperialism they preach concretes itself into the British Empire. Nationalist Ireland will not hearken, and Nationalist Ireland will be right, as it always is when it follows its instinct. It knows that the acceptance of the British Empire is the acceptance of English ascendancy. It will not accept that ascendancy, for its instinct warns it that to do so is death.

—The Irish Review, August 1911.

Constitutionalism and Parliamentarianism

No Irish Nationalist denounces constitutional action against England solely because it is constitutional. He merely declines to set it up as a fetish. If such action can aid the realisation of the National object it would be folly not to use it. On the other hand he will not hesitate to use unconstitutional action when he deems it well to do so.

—The United Irishman, April 29, 1899.

The UNITED IRISHMAN recognises as the most tremendous obstacle which besets this country in its fight for national existence, the Irish Parliamentary Party—distracting it by intestine feuds, denationalising and demoralising it by exalting London as its capital and the British Parliament as its Providence, betraying it by lending the sanction of Constitutionalism to foreign tyranny in Ireland, and degrading it by representing it to the world as a province pleading for concession, instead of a nation demanding its right. But the UNITED IRISHMAN belongs to no party, and has abandoned no policy. It has never advocated armed resistance, because—and only because—it knows that Ireland is unable at the present time to wage physical war with England. But it has been maintained and always shall maintain the right of the Irish nation to assert and defend its independence by force of arms—a right which no human being to whom God has given the ordinary complements of intelligence and honesty can venture to deny.

—The United Irishman, October 14, 1905.

These are the evil fruits of Parliamentarianism masquerading as Constitutionalism—physical and economic decay, moral debasement, and national denial.

—The Resurrection of Hungary.

We go to build up the nation from within, and we deny the right of any but our own countrymen to shape its course. That course is not England’s, and we shall not justify our course to England. The craven policy that has rotted our nation has been the policy of justifying our existence in our enemy’s eyes. Our misfortunes are manifold, but we are still men and women of a common family, and we owe no nation an apology for living in accordance with the laws of our being. In the British Liberal as in the British Tory we see our enemy, and in those who talk of ending British misgovernment we see the helots. It is not British misgovernment, but British government in Ireland, good or bad, we stand opposed to.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, address given to the First Annual Convention of the National Council in the Rotunda, November 28, 1905.

The issue for the Irish people, then, is that they should do nothing which would militate against their own right to set up a competent authority when this country shall be separated from England. For instance, the members of the police force are regarded as enemies of Ireland, which to a limited degree, and a limited degree only, they are. But the evil of this cast of thought is that the people may regard a police force of any kind as an evil to be combated, and that thus when a native government sends forth its decrees, which can only be enforced by a competent police force, it may find itself confronted and thwarted by this feeling which is in our day so well nurtured in the hearts of Irishmen.

—The United Irishman, January 5, 1901.

For generations Ireland has sent her elected representatives to the place where England breaks treaties—and now there are a quarter of a million less roof-trees in Ireland, millions of acres less cornland, and a million less men and women than there were on that fatal day in 1801, when, rejecting the shrewd advice of one wise Irishman, Irishmen entered the London Parliament, to be impotent of achievement and yet to sanction by their presence the imposition of a hostile and usurped authority upon our country.

—Nationality, March 24, 1917.

Economics and Trade Unions

I am in economics largely a follower of the man who thwarted England’s dream of the commercial conquest of the world, and who made the mighty confederation before which England has fallen commercially and is falling politically—Germany. His name is a famous one in the outside world, his works are the text-books of economic science in other countries—in Ireland his name is unknown and his works unheard of—I refer to Friedrich List, the real founder of the German Zollverein—the man whom England caused to be persecuted by the Government of his native country, and whom she hated and feared more than any man since Napoleon—the man who saved Germany from falling a prey to English economics, and whose brain conceived the great industrial and united Germany of to-day. Germany has hailed Friedrich List by the title of Preserver of the Fatherland, Louis Kossuth hailed him as the economic teacher of the nations. There is no room for him in the present educational system of Ireland. With List—whose work on the National System of Political Economy I would wish to see in the hands of every Irishman—I reject that so-called political economy which neither recognises the principle of nationality nor takes into consideration the satisfaction of its interests, which regards chiefly the mere exchangeable value of things without taking into consideration the mental and political, the present and the future interest and the productive powers of the nation, which ignores the nature and character of social labour and the operation of the union of powers in their higher consequences, considers private industry only as it would develop itself under a state of free interchange with the whole human race were it not divided into separate nations.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, address given to the First Annual Convention of the National Council in the Rotunda, November 28, 1905.

—Sinn Féin, September 13, 1913.

- That the true interests of Capital and Labour are not inimical but independent.

- That neither Capital nor Labour has fully realised the fact, and that the realisation must be forced upon them by the Nation.

- That in any pitched battle between Capital and Labour, with no intervening force, Capital must always win.

- That the Nation cannot afford that any one of its sections should be enslaved by the other, and therefore cannot permit such a pitched battle.

- That the right of Labour to a fair share of the joint product of Labour and Capital is clear and inalienable, and it is the duty of the Nation (or the State) to see that it gets it.

- That the Strike as a weapon of offence is useless and as a weapon of defence is only the last resort.

- That the path of progress for Labour is not along the line of destruction (the strike), since it cannot destroy without, like Samson, burying itself in the ruins, but along the line of construction (co-operation), by which it can bring its own strength gradually nearer to the level of the strength of Capital.

Against the Red flag of Communism which those responsible for the chaos into which Ireland has been plunged have not had the courage to unfold, we raise the Flag of an Irish Nation. Under that flag there will be protection, safety, and freedom for all. Tyranny, whether it be the tyranny of the capitalist or of the demagogic terrorist will find no shelter beneath the folds of the Irish nation’s flag. And for those who would bid this country bend the knee to the bloody idol of anarchy there is no room beneath a nation’s flag. The man who injures Ireland, whether he does it in the name of Imperialism or of Socialism, is Ireland’s enemy. The man who serves her whether he be a capitalist or a labourer, is her friend. Ireland lives to-day because not men of one class but men of all classes spent their lives in her service, and the man who tells the Irish people that Ireland must use all her energies to combat any foe other than the people of England who stand between Ireland and self-government, tells them the lie that maintains foreign rule in this country and keeps poverty enthroned in the most fertile island that the hand of God planted in the bosom of the Atlantic.

—Sinn Féin, September 30, 1911.

Imperialism and Socialism have offered man the material world—Nationalism has offered him a free soul, and Nationalism has won. Between the tyranny of the State and the soul of man stands the Nation.

—Sinn Féin, November 18, 1911.

Sinn Féin is a national, not a sectional movement, and because it is national it must not and can not tolerate injustice and oppression within the nation. It will not, at least through my voice, associate itself with any war of classes or attempted war of classes. There may be many classes, but there can only be one nation.

—Sinn Féin, October 25, 1913.

When Emmet died and Davis burned out his life and Mitchel descended into an English hell they did not die and labour and suffer to raise up in Ireland a replica of English civilisation—a State wherein many honest man starved while many a rascal flaunted the wealth of Croesus. But neither did they die and suffer so that their country might be delivered from the hands of one evil nation only that it might fall into the hands of men of no nation. They did not die and suffer for the tenant or the landlord, the workingman or the employer—they died and suffered for all, and the nation they saw in their prophetic eyes reared again upon this holy soil was a nation of men of many minds and many grades but of free hearts and manly brotherhood, nurtured in the love of justice and living by its law.

—Sinn Féin, October 25, 1913.

I affirm that the evils of the social system, as they exist in this country and in Great Britain, are wholly due to English policy and Government, and that that policy and that Government are partly responsible for those evils, as they exist, though in a modified form, outside the radius of the British flag. I deny that Socialism is a remedy for the existent evils or any remedy at all. I deny that Capital and Labour are in their nature antagonistic—I assert that they are essential and complementary, the one to the other.

—Sinn Féin, October 25, 1913.

The free nation I desire to see rise again upon the soil of Ireland is no offspring of despair—no neo-feudalism—with Marx and Lassalle and Proudhon as its prophets. It is the ancient Irish nation called into new being—a nation in which there will be no slums and no hunger, and every honest man who labours and performs will live in comfort and security. I am not concerned with the interests of humanity at large. I am concerned with the interests of my own people. But this I know—that he who wishes to serve humanity at large can only do so effectively when he serves it through the nation.

—Sinn Féin, October 25, 1913.

If there be men who believe that Ireland is a name and nothing more, and that the interest of the Irish workman lies, not in sustaining the nation, but in destroying it, that the path to redemption for mankind is through universalism, cosmopolitanism, or any other ism than nationalism, I am not of their company. I have never been of their company. I never shall be of their company.

—Sinn Féin, October 25, 1913.

It has been recently discovered that the Irish workingman is not an Irish workingman at all. He is a unit of humanity, a human label of internationalism, a Brother of the men over the water who rule his country. There is nothing to divide him from them except a drop of water. Race, tradition, nationality, are non-entities, and history and its formative influences on character and outlook a figment. He is exalted from the meaningless title of Irishman to the noble one of Brother. His Brothers were formerly called Englishmen, and under that title were improperly regarded by him as his enemies. As Brothers it is obvious they are his friends. They have counselled him to no longer darken his mind by repeating the reactionary and unenlightened shibboleth, ‘Ireland for the Irish.’ ‘You do not,’ they say reprovingly, ‘hear us crying, ‘England for the English,’ which is quite true, as they have got it already and will hold on to it like leeches until the boot of the Kaiser is strong enough to dispossess them.

—Sinn Féin, October 4, 1913.

We produce in this country a number of people believing themselves thinkers and Nationalists who think the thoughts of third-rate Englishmen and whose nationalism begins and ends with a desire for freer political institutions in Ireland. They are sincere people; but they have been a potent Anglicising influence in this country, and it is to them we owe the great economic delusion which held, and partially still holds, Ireland in its grip.

—Sinn Féin, July 24, 1909.

Irish History

The true use of history, then, is to recognise beneath all the vandal plaster of modern word-spatterers the unity and continuity of our ideal—how our public men in the past strove for it; how far they approached it. We will note their mistakes and try to avoid their recurrence. One Treaty of Limerick ought to be enough in the lifetime of the Irish nation.

—The United Irishman, December 23, 1899.

The people will sift the chaff from the grain, and though the worthless and the wicked be glorified for a time by magnificent monuments adorned with grandiloquent epitaphs, the Irish people will treasure up the memory of those whose principles are theirs, and whose epitaph will be written when we, following those principles, will achieve National freedom. A day may come to witness an Irish Westminster, an Irish Pantheon, but it will not more reflect the hallowed memory of the dead than at present dwells in our hearts. But it will do then what now is impossible; marking the advent of our freedom, its cenotaphs will breathe an inspiration to many a rising generation, bidding them to go forth and emulate those who here rest in final repose, by advancing the prowess and glory of the Irish Nation!

—The United Irishman, August 18, 1900.

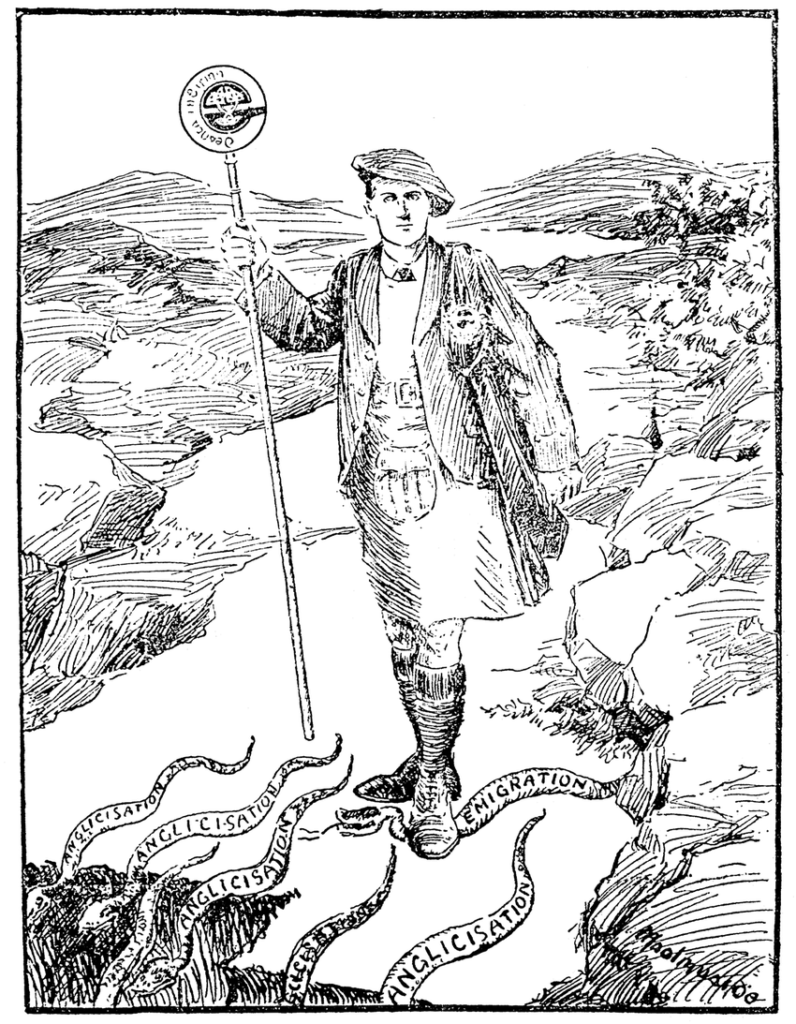

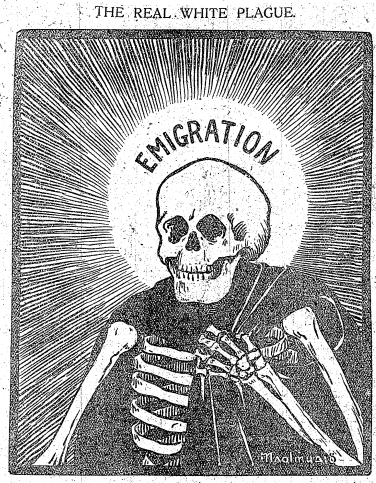

Emigration

The folly is dead now—so dead that most have forgotten it ever existed, but the evil remains. We have, however, a united opinion against emigration. Nationalist and Unionist, Catholic and Protestant, alike deplore it… The English Government is not going to legislate against emigration from Ireland. If it does not work to stimulate it, it will remain inactive.

—Sinn Féin, August 27, 1910.

On the walls of hundreds of schools in this country advertisements of emigration—mainly to Canada—are displayed before the pupil’s eyes day by day. For the years of his or her school life the boy or the girl has it day by day burned into the mind, if not by word of mouth by as dangerous a method, that this is a country to get out of, and that it is natural and proper for one to get out.

—Sinn Féin, August 27, 1910.

Now, let us consider the poor law system of this country. Like the education system, it was forced upon us by England, and with an equally sinister object. It has been a potent instrument for pauperising and demoralising the people. From 1846 to 1849 it was used as a machine for forcing the small farmers of Ireland into the workhouse or into the emigrant ship by the imposition of a crushing poor-rate. Since that period it has been used to impoverish the country by expending its money on foreign goods and by subsidising emigration, and to debase the spirit of the people by stamping pauper on the brow of every honest man and woman whom circumstances may for a period render dependent on the assistance of their fellow-citizens.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

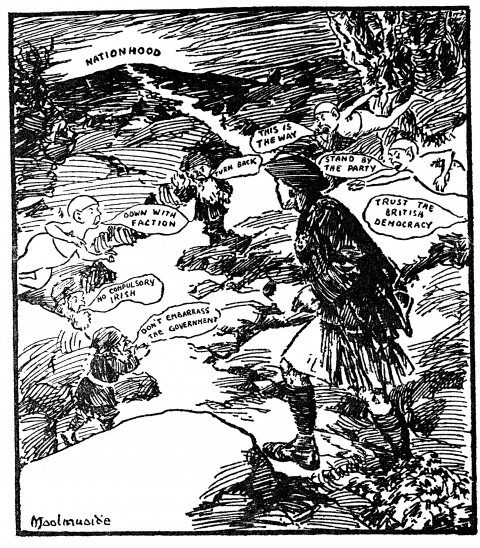

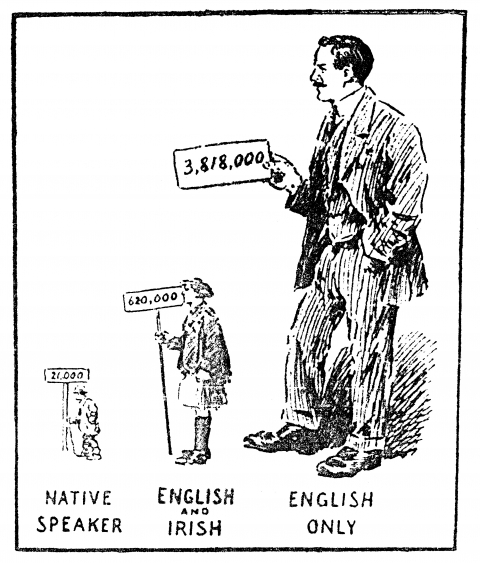

An Ghaeilge / The Irish Language

The language movement has stirred the dormant spirit of the race, and lifted them out of the rut of disorganised and hopeless Parliamentary agitation, whose futility and lack of progress has filled the nation with despair, till our people once again breathe freely with a breath of hope, for they see now that something may be done without the hallmark of Westminster on the programme, and when something may be done, who shall say that more and more may not? Who shall dare to put a limit to the progress of a re-awakened nation in the first realisation of the power that is in it?

—The United Irishman, December 1, 1900.

Every Irish Nationalist desires the restoration of his country’s independence and his country’s language. But if our independence were to be gained only by destroying our language, I would take a hatchet myself and go forth to destroy. Nor would any Irish Nationalist hesitate a moment to choose between an independent Ireland, with its own Government, its own flag, its own army and its own fleet, speaking English, and an Ireland bringing forth Irish-speaking fusiliers to do England’s bloody will. Fortunately, there is no need to make a choice. Irish Nationalism and the Irish language go hand-in-hand.

—The United Irishman, January 12, 1901.

An Irish independent State speaking the English language is possible, but an Irish nation is not possible without the Irish language. Two nationalities coalescing may produce a new nation, as Normans and Saxons made the English nation and Gauls and Romans made the French nation. But an English-speaking Ireland or a German-speaking Poland is not and cannot be an Irish or a Polish nation. Here there is no marriage, no coalescence—but absorption and national extinction.

—Sinn Féin, November 18, 1911.

Protectionism

An agricultural nation is a man with one arm who makes use of an arm belonging to another person, but cannot, of course, be sure of having it always available. An agricultural-manufacturing nation is a man who has two arms of his own at his own disposal… Let the Irish people get out of their heads the insane idea that the agriculturing and manufacturing industries are opposed. They are necessary to each other, and one cannot be injured without the other suffering hurt. We must further clear their minds of the pernicious idea that they are not entitled or called upon to give preferential aid to the manufacturing industries of their own country.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

We must offer our producers protection where protection is necessary; and let it be clearly understood what protection is. Protection does not mean the exclusion of foreign competition—it means rendering the native manufacturer equal to meeting foreign competition. It does not mean that we shall pay a higher profit to any Irish manufacturer, but that we shall not stand by and see him crushed by mere weight of foreign capital. If an Irish manufacturer cannot produce an article as cheaply as an English or other foreigner, only because his foreign competitor has larger resources at his disposal, then it is the first duty of the Irish nation to accord protection to that Irish manufacturer. If, on the other hand, an Irish manufacturer can produce as cheaply, but charges an enhanced price, such a man deserves no support—he is, in plain words, a swindler.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

Having thrice within three hundred years destroyed Irish commercial and industrial prosperity by force and fraud—having, in defiance of engagements, made Ireland jointly responsible for England’s National Debt—having made, in the words of Nassau Senior, Ireland the most heavily taxed and England the most lightly taxed country in Europe—England has represented Ireland to the world as a naturally poor and incapable country, kept from want by English benevolence. Ireland is not the only country whose commerce and industries were forcibly repressed by a jealous rival; nor is she the only country whose soil was confiscated to foreign adventurers; possibly she may not be the only country where a price was placed by its foreign rulers on the schoolmaster’s head; but the Irish people are the one people on the earth to-day whose education, commerce and industry having been repressed, are held up by the repressors to the scorn of the world as a lazy, idle, poverty-stricken and illiterate people.

—The Economic Oppression of Ireland, 1918.

We are Protectionists. If we could we would seal the ports of Ireland for ten years against aught but the raw materials we need and which our country does not produce.

—The United Irishman, November 11, 1905.

Education

The National Civil Service of Ireland will demand no more than the National Civil Service of any country on the Continent of Europe does—that its members must know all about it. Institute a National Civil Service in Ireland, and the English education system of this country, designed to suppress in the breasts of its people the impulse of patriotism is revolutionised. If no position in the public service of Ireland can be obtained by those ignorant of Ireland, the schools must teach Ireland—and must teach their pupils Ireland’s history, Ireland’s language, and Ireland’s possibilities. A National Civil Service in Ireland will provide a bulwark to the nation—it will revolutionise the so-called educational system—it will save for Ireland thousands of men who unwillingly leave it—it will necessarily cause the uprise of the most Irish-educated generation Ireland has known for centuries. It means an educated Ireland, and an educated Ireland is the harbinger of a free Ireland.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

University education in Ireland is regarded by the classes in Ireland as a means of washing away the original sin of Irish birth. It is founded on the inversion of Aristotle, as indeed the three systems of education in Ireland are. The young men who go to Trinity College are told by Aristotle that the end of education is to make men patriots; and by the professors of Trinity not to take Aristotle literally. Education in Ireland encumbers the intellect, chills the fancy, debases the soul, and enervates the body. It cuts off the Irishman from his tradition, and by denying him a country debases his soul, it stores his mind with lumber and nonsense, it destroys his fancy by depriving him of tradition, and enervates his body by denying him physical culture. Sir, this is the education which, as Aristotle says, ruins the individual and eventually the nation. If he lived in our times and our country, Aristotle would be a seditious person in the eyes of the British Government in Ireland, which makes him useful to it now by standing him on his head.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

How are we to remedy these things? As to primary education, a friend of mine in London has made suggestions which I believe are practicable. If the control of primary education is not voluntarily transferred from the British Government in Ireland to the Irish people, let the Irish people take over the primary education system themselves. They can do this in the first place by transferring, where possible, the pupils of the ‘National’ schools into the schools of the Irish Christian Brothers, and where this is not possible, by founding voluntary schools, sustained in part by the contributions of the parents and part from a National Education Fund subscribed to annually by the Irish people throughout the world. Is this considered impossible? Hungary did it forty years ago—Poland did it but yesterday, and the one overthrew Austria, as the other is overthrowing Russian autocracy.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

Foreign Policy

At the present time Ireland has little trade with any outside country, not because she does not produce many things which they require and which they buy, but because England blocks the way with her middleman’s profit. So long as Ireland has no mercantile marine of her own and no consular representation abroad, this must remain the case. The British Consular service is run solely in the interests of Britain, but Ireland is taxed to pay for its upkeep.

—The Sinn Féin Policy, November 28, 1905.

Nature put the keys of the commerce of Europe and America into Ireland’s hands, and English policy, aiming at the commercial subjugation and exploitation of the world, first aimed at the subjugation of Ireland. Ireland’s position, the fact that she commands the ocean routes, that her bays and harbours are the finest in Europe, and that she possesses within herself the resources of a great maritime nation—is the explanation of her continued suppression and oppression.

—Nationality, January 22, 1916.

Briefly, I propose the formation of a National Republican organisation in Ireland, pursuing for the present a British-law-abiding and educational policy in Ireland and cultivating also an Irish foreign policy. To outline one here is not, at present, necessary. It is sufficient to know that Ireland can make its power felt in every division of the world save, perhaps, one, and can make itself an object of concern to England’s three great European enemies—Russia, France, and Germany.

—The United Irishman, April 29, 1899.

On Irish Nationalists

I believe the Irish people made themselves ridiculous by their treatment of Charles Stewart Parnell. He had committed no political crime. He had not sinned against them. If he deserved stoning to death, it was not the Irish people who had the right to be his executioners.

—The United Irishman, May 19, 1900.

Be it as it may, Parnell hated the English and English ways as much, if not more so, than if he had been inoculated with the spirit of Hugh O’Neill, or with the fiery doctrines of Wolfe Tone. All English statesmen bear testimony to the fact. But some pass the verdict that he hated England more than he loved Ireland. However, any man, no matter his nationality, who bitterly hates England, and tries to work her undoing is well acceptable to Irishmen; and if, moreover, he happens to be an Irishman himself, even in birth only, his credentials to our admiration are full and complete, and deserving of our confidence.

—The United Irishman, July 21, 1900.

Davis was the first public man in modern Ireland to realise that the Nation must be rebuilt upon the Gael. Neither Grattan nor Wolfe Tone, both of whom sought like Davis to unite Catholic and Protestant, Cromwellian and Milesian in the common bond of country, realised as Davis did that while it is impossible to undo the Plantations, it is essential to undo the Conquest.

—Thomas Davis: The Thinker and Teacher, 1914.

Mitchel died as he lived, in battle with his country’s enemies. Gifted with all the qualities of greatness, but lacking personal ambition, passionate love of his country and fierce indignation at her oppression impelled him into her public life, and in all her public life no character stronger and purer can be found. He strove to breathe the fire of his own soul into his country-men, and his spirit redeems the most humiliating page of Irish History in the nineteenth century.

—Preface to Jail Journal by John Mitchel, 1913.

So long as the spirit of Fenianism diffused itself through the body politic, Ireland marched on a hundred paths of political, social, industrial, and educational effort to National Regeneration. When the body grew corrupt Ireland shrivelled in men’s minds from a spiritual force and a National entity to a fragment of Empire—an Area. Again, the Body Politic has healed and awakens to consciousness of that soul within it which the Political Atheist denies. No man will watch the body of O’Donovan Rossa pass to its tomb without remembering that the strength of an Empire was baffled when it sought to subdue this man whose spirit was the free spirit of the Irish Nation.

—The Influence of Fenianism, 1915.

Ulster Unionism

Is it not infinitely degrading to the common sense as well as to the status of Irishmen that they should discuss their own affairs from the standpoints of English party? If there be sound arguments against Home Rule, they are to be urged from the standpoint of Ireland’s interest. As yet I have heard none. I have heard it foretold that an Irish Parliament will persecute and plunder men because of their religious convictions—and I have seen it stated by the same people that the hapless minority which must inevitably suffer persecution under Home Rule is strong enough to face and beat the British Empire in arms. With scaremongers and fools there can be no reasoning.

—The Irish Review, May 1912.

But so far as it is articulate Ulster Unionism is opposing not merely this paltry measure, but the principle of National self-government in Ireland. If Irish Nationalists acquiesced in the claim of a small minority to veto their country’s rights, check its aspirations, or disintegrate its territory, they would be slavish indeed… No man by reason only of his being Catholic or Protestant, Unionist or Nationalist, Ulsterman or Leinsterman is the superior of his fellow Irishman. To allow for fears, distrust, ignorance, is good statesmanship, and good patriotism. To submit to an arrogant and unfounded claim is bad statesmanship and no patriotism at all.

—Sinn Féin, May 2, 1914.

Our Unionist fellow-countrymen sometimes ask what guarantee they can have that they would be fairly represented in an Irish Parliament. We reply that Irish Sinn Féiners are ready to accept the principle of proportional representation, and approve the scheme of Mr. Dobbs. If they are still timid and distrustful of their countrymen, will they let us know what additional security their distrust requires?

—Sinn Féin, May 2, 1908.

To our Unionist fellow-countrymen—the bulk of whom we believe to be honest Irishmen—we send a challenge, not in enmity, but in comradeship—You allege that Irish nationalism thrives only on the exploitation of Irish grievances: well, unite with us to remove these grievances, and having removed them fight out the issue between us on the principle that underlies them—free from all entangling sub-issues.

—Sinn Féin, October 10, 1908.

Sinn Féin is not the Nation. Parliamentarianism is not the Nation, Unionism is not the Nation—all are but weapons offered to the Nation; and, by their effectiveness in the Nation’s service, they must be judged and retained or discarded. The Nation belongs exclusively to none of us, Nationalists or Unionists, Catholics or Protestants, rich or poor—it belongs to us all, and it is greater than us all. The party comes and goes—the Nation remains for ever.

—Sinn Féin, August 24, 1909.